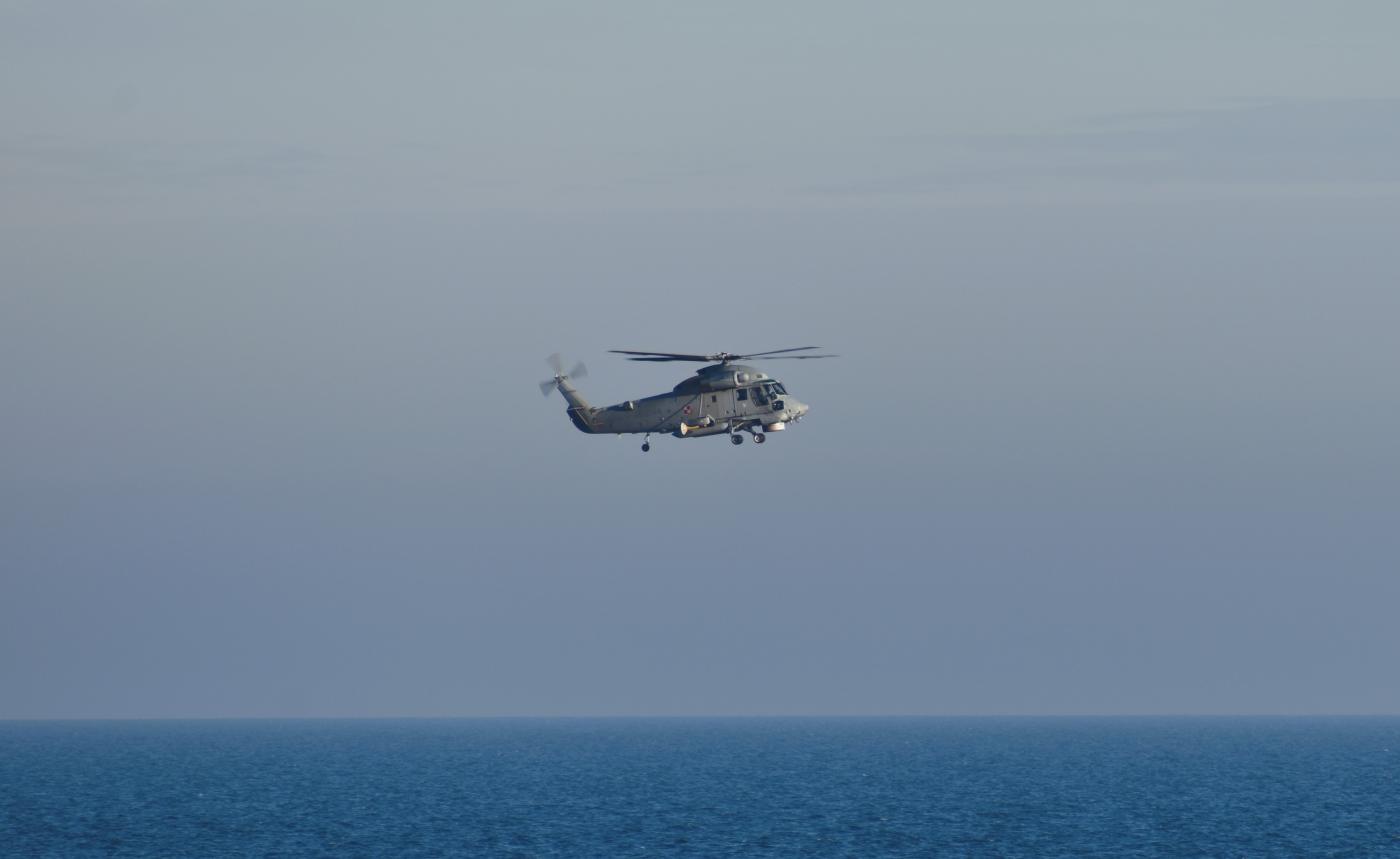

End of an era for Polish naval aviation: SH-2G Super Seasprite retires

After more than two decades of service, the SH-2G Super Seasprite helicopters operated by the Gdynia-based Naval Aviation Brigade are marking the symbolic end of an era in Polish naval aviation. These rotorcraft entered Polish service in the early 2000s, following the acquisition of two Oliver Hazard Perry–class frigates — ORP Gen. K. Pułaski (272) and ORP Gen. T. Kościuszko (273).

aviation navy pomerania west pomerania equipment and technology news08 november 2025 | 15:26 | Source: Gazeta Morska | Prepared by: Kamil Kusier | Print

fot. Kamil Kusier / Gazeta Morska

Poland procured four SH-2G helicopters in total — two delivered in September 2002 and two in August 2003. Designed for maritime operations, the type was employed in anti-submarine warfare (ASW), surface surveillance, and naval support missions.

Over time, however, sustaining operations became increasingly challenging. With the manufacturer ceasing technical support, spare parts grew scarce, and aging airframes reduced operational availability. In recent years, only one or two aircraft remained airworthy, with the others serving as parts donors. Although the Ministry of National Defence announced plans for their retirement back in 2018, the process now formally concludes.

While expected, the withdrawal marks a significant transition point — closing a chapter in the history of Polish naval aviation. The SH-2Gs served alongside warships for years, participating in national and allied exercises, Baltic patrols, and overseas deployments. Their service will remain an integral part of the Polish Navy’s legacy.

Project “Kondor”: the long-awaited successor

To fill the capability gap left by the SH-2G, the Polish Ministry of National Defence launched Project “Kondor” — a program aimed at acquiring new, multi-role shipborne helicopters capable of operating from frigate decks.

The preliminary concept foresees the procurement of four to eight helicopters with a maximum takeoff weight of approximately 6.5 tons, optimized for ASW and maritime reconnaissance missions.

Participants in the technical dialogue included both domestic and international entities: PZL-Świdnik, PZL Mielec, Polska Grupa Zbrojeniowa, as well as Airbus Helicopters, Bell Textron, Leonardo Helicopters, and Kaman Aerospace.

Although the procedure was officially launched on 29 December 2019, and the technical dialogue was planned for 2020, the process faced multiple delays — driven by evolving requirements, the need for local industrial participation, budgetary constraints, and shifting modernization priorities.

As of today, no executive contract has been signed. The absence of new platforms raises the risk of a capability gap in shipborne aviation within the coming years.

Financial leverage through the SAFE instrument

A potential accelerator for Project Kondor could come from the EU SAFE (Security Action for Europe) financial instrument, established to promote joint defense procurements and strengthen Europe’s defense industrial base.

SAFE allocates up to €150 billion, with approximately €43.7 billion available to Poland through preferential loans and grants.

For Kondor, this opens an opportunity to co-finance helicopter acquisition as part of a joint European program — provided Poland prepares a compliant proposal meeting SAFE’s criteria: joint procurement, industrial participation, and adherence to approved timelines.

This represents a real window of opportunity — one that requires swift and coordinated action by the MoD and the domestic defense industry.

Successor candidates: options for the Polish Navy

Several contenders are viewed as viable replacements for the SH-2G, suitable for integration with the Pułaski/Kościuszko frigates and the future Miecznik-class vessels.

Leonardo AW159 Wildcat / AW101 Merlin

- Compact, fully navalized ASW/ASuW platform in service with the Royal Navy.

- Poland already operates four AW101s (ASW/SAR configuration), simplifying logistics and training.

- Unit cost: approximately USD 50–60 million, depending on configuration.

Airbus H160M Guépard / AS565 Panther

- Modern, lightweight maritime helicopters with advanced avionics, optimized for smaller decks.

- H160M offers multi-role potential with ASW equipment integration.

- Estimated cost: USD 40–55 million per unit.

Bell UH-1Y Venom / MH-60R Seahawk

- UH-1Y: versatile and highly reliable multirole helicopter compatible with U.S. ship systems.

- MH-60R: the world’s most advanced ASW helicopter, fielded by the U.S. Navy, Australia, and Denmark.

- Full-package cost (including logistics and armament): USD 70–90 million per aircraft.

Program costs and feasibility

Assuming the procurement of 4–8 helicopters under Kondor, total costs are estimated at:

- AW159 / H160M: PLN 1.2–2.5 billion for four units

- MH-60R / AW101: PLN 2.5–5 billion for four units

A full eight-aircraft fleet could therefore cost PLN 2–6 billion, making the program financially achievable with EU SAFE co-funding.

The need for timely decisions

The retirement of the SH-2G marks both a challenge and an opportunity. Without replacement, the Navy risks losing its organic ASW and maritime surveillance capabilities.

Project Kondor must therefore gain momentum. Leveraging SAFE could provide not only financial relief but also technological and industrial benefits.

Key selection criteria should include multi-mission flexibility (ASW, ISR, ship support), full integration with Miecznik-class frigates, domestic industrial participation (assembly, maintenance, lifecycle support), and a comprehensive logistics and training package ensuring 20–30 years of operational sustainability.

Alignment between Kondor and Miecznik programs will be essential to synchronize ship and helicopter combat readiness.

Investing in people and capability

The Gdynia Naval Aviation Brigade now awaits decisive action. While the SH-2G Super Seasprite retires with honor, the Navy must ensure continuity in shipborne helicopter operations.

With timely decisions and effective use of available EU instruments, Poland can not only replace outdated assets but also build a modern, integrated maritime aviation capability supported by domestic industry and international cooperation.

Polish naval aviators — highly trained, experienced, and respected within NATO — deserve equipment that matches their professionalism and dedication.

Ultimately, it is people — their skill, determination, and service — who remain the greatest strength of the Polish Navy. Modernization should therefore be seen not only as an investment in technology, but above all in the safety, capability, and professionalism of those who safeguard Poland’s seas and skies.

see also

Buy us a coffee, and we’ll invest in great maritime journalism! Support Gazeta Morska and help us sail forward – click here!

Kamil Kusier

redaktor naczelny

gallery

comments

Add the first comment

see also

"Let everyone know we will prevail". Poland’s armed forces set strategic course for 2026-2039

“Army 500” and strategic transformation: Poland sets the course for long-term deterrence and allied readiness

Medical evacuation from Danish-flagged vessel Skoven off Łeba. Joint SAR operation in the Baltic Sea

SAR medevac operation in the Baltic Sea: m/v Lone crew member airlifted to Słupsk hospital

Polish Navy conducts medical evacuation from Aura Seaways ferry in harsh Baltic conditions

Polish naval aviators conduct another medical evacuation operation in the Baltic Sea

NHV launches helicopter base in Gdańsk to support Baltic offshore wind sector

Medical evacuation from offshore installation in the Baltic Sea. First naval SAR mission of 2026

The capture of President Nicolás Maduro: how U.S. maritime operations triggered a geopolitical turning point

Kondor over the sea: Poland’s attempt to close the maritime situational awareness gap

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT