Four apocalypses that never happened

In the ancient myth of Damocles, a courtier of the Syracusan tyrant Dionysius dreamed of power and wealth. When the king granted him a brief taste of the throne, Damocles noticed a sword dangling above his head, held by a single horsehair. He realized then that power comes with the constant threat of ruin. This image—a sword teetering between might and disaster—became a timeless metaphor, gaining new weight in the nuclear age. Today, humanity lives under a nuclear Dam, capable of ending life in an instant, whether through a struggle for dominance, a simple misunderstanding, or a trivial error.

security education other worldwide opinions and comments commentary news20 march 2025 | 14:28 | Source: Gazeta Morska | Prepared by: dr Paweł Kusiak | Print

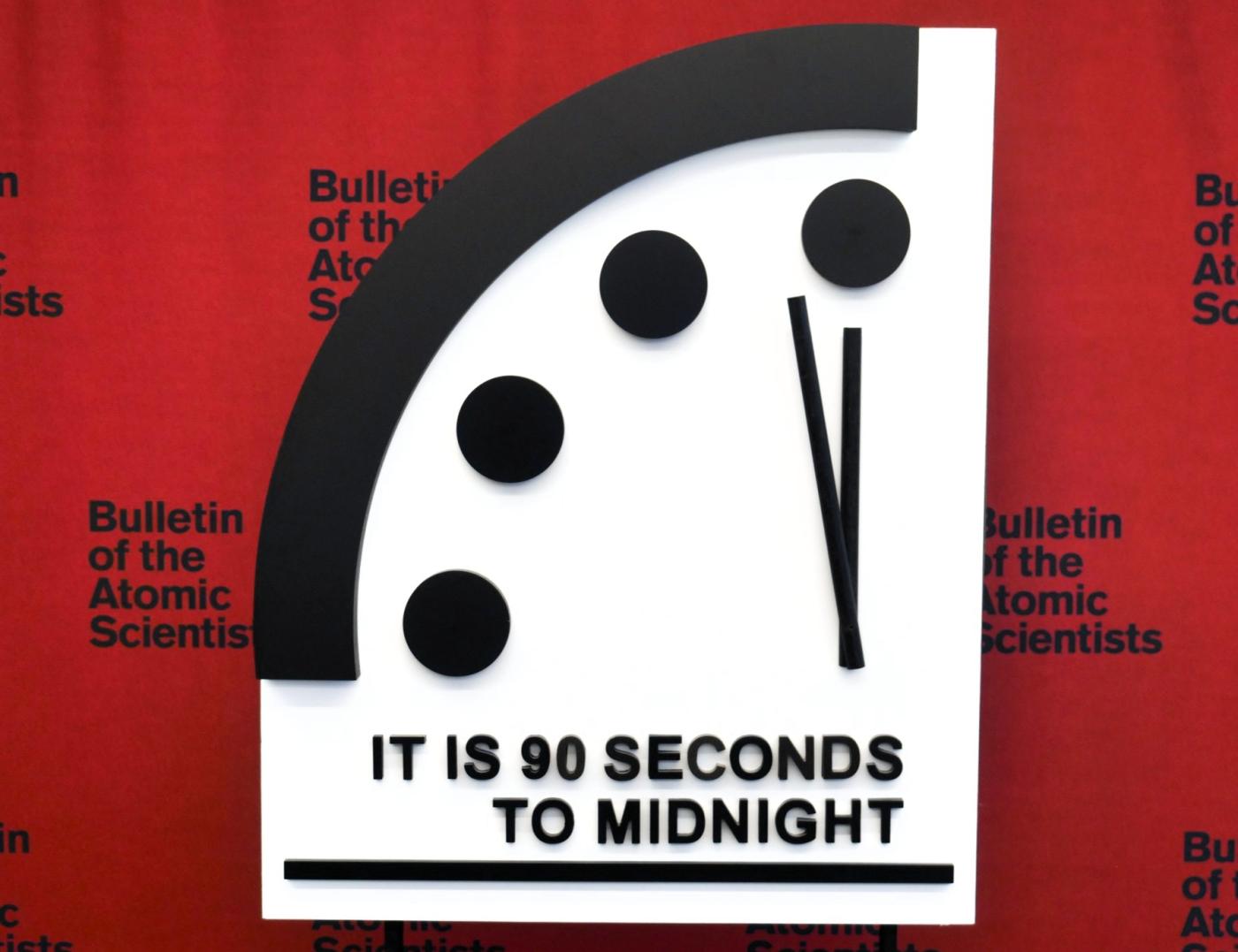

Zegar zagłady ang. Doomsday Clock | fot. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

Why has the sword never fallen on our heads? The answer lies in systems, protocols, and countless decisions made by political and military leaders of nuclear superpowers. But history also records moments when anonymous individuals, acting alone or in small groups, made decisions that averted global nuclear war. Each of them, in a way, lived like Damocles—one wrong move could have destroyed not just our world as we know it, but the world itself.

1962: commander Vasili Arkhipov and the power of mental resilience

The Cuban Missile Crisis is widely considered the moment when the world came closest to nuclear war. One of its most critical events took place on October 27, 1962. On that day, Soviet submarine B-59 found itself under attack by U.S. destroyers, which, unaware of its nuclear payload, dropped depth charges to force it to the surface. Inside B-59, the exhausted and psychologically drained crew believed war had already begun. The submarine’s captain and political officer agreed to launch a nuclear torpedo in retaliation. Given the circumstances, such an attack would have almost certainly triggered an all-out nuclear war—one the U.S. could not have ignored.

But the torpedo was never launched. Soviet protocol required unanimous approval from three officers to use nuclear weapons. The third officer, commander Vasili Arkhipov, made the crucial decision to oppose the strike. Despite the unbearable tension, the stress, and the lack of clear information, he relied on instinct and reason. He refused to authorize a nuclear launch based on the limited data at hand. One can only imagine what he felt at that moment—fear, duty, responsibility? In 2002, Thomas Blanton, director of the U.S. National Security Archive, put it bluntly: "Vasili Arkhipov saved the world." And he truly did.

The alarms that almost ended the world

Why has the sword never fallen on our heads? Some would say there are no coincidences, only signs. People often use this idea in a religious or philosophical sense—to make sense of an uncertain world, to rationalize it, to feel in control. If everything happens for a reason, then our lives must have meaning too.

Perhaps that’s how we should look at what happened in NORAD on November 9, 1979, and later in the Soviet Union on September 26, 1983. In both cases, the world came terrifyingly close to nuclear war—not because of war-hungry leaders, but due to system failures and human error. And in both cases, we were saved by individuals who kept their cool in moments of extreme pressure.

1979: the NORAD alarm that wasn’t a mistake

On November 9, 1979, a chilling scene unfolded inside the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD). The center’s computer systems detected a full-scale Soviet nuclear attack on the United States. Hundreds of incoming warheads appeared on radar screens, signaling an impending catastrophe. Panic set in. Strategic bomber crews rushed to their planes, nuclear force commanders awaited the order to retaliate, and the countdown to global annihilation had begun.

Yet, in this critical moment, a few high-ranking officers noticed a strange inconsistency—ground-based radars showed no actual missile launches. Instead of blindly trusting the computer-generated alarm, they initiated additional verification steps. Soon, they uncovered the terrifying truth: a technician had accidentally inserted a training tape into the system, which the computer had interpreted as a real attack.

Had someone panicked and ordered a counterstrike, the U.S. could have launched a nuclear assault in response to a war that existed only inside NORAD’s computers. The Soviet Union would have retaliated, and the world as we know it would have ceased to exist. Would anyone have been left to wonder whether it was all a coincidence or a sign? No one can say.

1983: Colonel Stanislav Petrov and the weight of experience

Patterns can be both a blessing and a curse. They help structure our decisions, speed up responses, and minimize errors—but they also foster rigidity, stereotypes, and dangerous assumptions. In times of crisis, they can be fatal.

On September 26, 1983, inside a Soviet nuclear warning center, a chilling message appeared on the control screen: the United States had launched ballistic missiles. It was the middle of the night, and Cold War tensions were sky-high after the Soviet Union had shot down a South Korean passenger plane just weeks earlier. The world was on edge, and Soviet military leadership was ready for the worst.

One man held the power to confirm the attack: Colonel Stanislav Petrov. He had only minutes to decide whether to report the warning to the Kremlin, which could have triggered a Soviet nuclear response.

But something felt off. Petrov hesitated. Why would the U.S. launch only a few missiles? Every nuclear war scenario he had studied predicted a massive first strike, not a limited attack. A single missile launch would be suicidal—because the other superpower would survive and strike back with full force. The situation didn’t add up.

Petrov made a critical decision against protocol: he declared the alarm a false alert.

And he was right. The "attack" was caused by a satellite system failure, which had mistakenly interpreted sunlight reflections as missile launches. But at that moment, Petrov didn’t know that. For a few brief minutes, he alone held the fate of the world in his hands.

The night passed. The sun rose again. And the sword remained where it was—dangling, but still unswayed.

1995: Yeltsin and the Russian nuclear briefcase

On January 25, 1995, Norwegian scientists, in collaboration with NASA, launched a Black Brant XII meteorological rocket from the Andøya Space Center in northern Norway. The rocket's mission was to study the aurora borealis and atmospheric conditions in the upper layers of the atmosphere. However, by sheer coincidence, its trajectory resembled the flight path of an American Trident ballistic missile, which, in the event of war, could be launched from a submarine off the coast of Norway.

Immediately after launch, Russia’s warning systems detected the rocket and identified it as a potential ballistic missile launched from Norwegian territory. The trajectory suggested that it could be a nuclear attack, possibly intended to create an electromagnetic pulse (EMP) over Moscow. Within minutes, Boris Yeltsin activated the so-called "nuclear briefcase", a system allowing for the launch of Russian nuclear missiles in retaliation.

Yeltsin now faced a momentous decision—whether to follow the doctrine of mutual assured destruction (MAD). The principle of MAD dictates that if a nuclear-capable state is attacked, it will retaliate regardless of the consequences, ensuring the total annihilation of both the attacker and the defender. It is worth noting that Russian military leaders were particularly concerned about the possibility of a decapitation strike—a precise nuclear attack by the U.S. aimed at eliminating Russia’s leadership in one blow.

At first glance, all the conditions for a global nuclear war appeared to be in place. The world could have gone up in flames within minutes, and during that brief window, Yeltsin alone held the power over life and death. The crisis was ultimately defused when intelligence reports confirmed that the rocket was not heading toward Russia. It was, in fact, a Norwegian scientific probe, the launch of which had been previously reported to Russia—but the information never reached the appropriate officials. The misunderstanding was resolved, and the crisis was averted.

Can we get used to living in the shadow of nuclear annihilation?

Historical cases of false nuclear alarms reveal a harsh truth about the weakness of nuclear deterrence based on rapid response. Each analyzed situation is unique, yet they all share a fundamental truth about the world and the moral choices of individuals.

In 1962, the crisis was triggered by a lack of access to information. It was resolved—at least based on what we know—due to the individual character traits of Commander Arkhipov, who resisted the pressure from his commanding officer and political officer. In 1979, a computer failure at NORAD caused a false alarm, but the mistake was detected and corrected by people who refused to blindly trust the system. A similar situation occurred in 1983, when Colonel Petrov’s knowledge and experience prevented a catastrophic decision. That case served as a vaccine against excessive trust in radar data.

The 1995 incident was slightly different: the decision not to launch a counterstrike was made after confirming that the rocket was not heading toward Russia. This is the only case among those discussed where the decision was based on clear, objective evidence (or so it seems). However, this was only possible because such evidence became available. Had the rocket's trajectory remained ambiguous, Yeltsin would have been forced to stare at the Damocles' sword hanging over him—and the world.

Key lessons from false nuclear alarms

From these historical cases, we can draw several key conclusions:

- The role of individuals—decisions made by a single person can prevent disaster.

- The importance of rigorous technical safeguards—systems should not rely solely on automated responses.

- The doctrine of nuclear weapons use—the speed of a nuclear response can make mistakes irreversible.

- The necessity of dialogue between nuclear powers—misunderstandings can have catastrophic consequences.

An additional concern in this context is the role of artificial intelligence (AI), which has become a defining factor in modern technological progress. Let’s hope that we never delegate full control over nuclear arsenals to AI, as films like WarGames (1983) have already warned us.

Can we get used to living under the threat of nuclear war?

It is said that humans can get used to anything. After all, we rarely think about it in our daily lives. We don’t think about it because, as a rule, people don’t dwell on things they have little or no control over.

For those who do lose sleep over the threat of nuclear annihilation, there is the Doomsday Clock, a project by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists at the University of Chicago, established in 1947. The clock serves as a symbolic indicator of how close humanity is to a potential global catastrophe. Midnight represents the moment of destruction, while the number of minutes (or seconds) to midnight reflects the current level of risk.

In January 2025, the Doomsday Clock was set to 89 seconds to midnight. Is that a lot or a little? After the Cold War ended and the START I treaty was signed between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, the clock was set at 17 minutes to midnight—meaning the situation has worsened by more than 15 minutes since then.

The worst moment during the Cold War was 1953, at the height of hydrogen bomb tests, when the clock stood at 2 minutes to midnight. As we can see, today's situation is the most dangerous in history.

To be precise, the Doomsday Clock doesn’t measure only the threat of nuclear war but also considers climate change and technological disruptions. Regardless of the cause, let’s hold on tight…

Dr. Paweł Kusiak

expert at Daily Mare

see also

Buy us a coffee, and we’ll invest in great maritime journalism! Support Gazeta Morska and help us sail forward – click here!

Redakcja Gazeta Morska

użytkownik

comments

Add the first comment

see also

Polish Naval Academy and Institute of Fluid-Flow Machinery establish research partnership

SAR search operation in the port of Władysławowo. man who fell into the water not found

Medical evacuation from Wind Osprey underway as winter keeps Polish SAR services under pressure

Coast Guard ensures fishermen safety on the ice of the Vistula Lagoon Select 81 more words to run Humanizer.

Services on ice. False alarm in Swarzewo in Poland. Such behavior endangers those who truly need help

PIRANIA underwater inspection vehicle: Gdańsk University of Technology and Radmor join forces

Grupa WB joins ASD. Strengthening Central and Eastern Europe’s voice in the European defence industry

Poland’s security in focus. President meets with ministers and heads of special services

NATO’s persistent naval presence in the Arctic and the northern Atlantic strengthens sea lane security

Poland launches second DELFIN SIGINT ship ORP Henryk Zygalski in Gdańsk

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT